Suspicious Activity Reports, known as SARs, burst onto the political scene in 2018 during the Mueller Special Counsel investigation of former President Trump when a Treasury Department employee leaked confidential documents to BuzzFeed. The U.S. House of Representatives Judiciary Committee’s investigation of Hunter Biden has put SARs back into the news. Because banking is one of the most heavily regulated industries in the country, banking lawyers and litigators who go to court for banks, need to know what SARs are, when the mere existence of a SAR may be acknowledged or disclosed, and how to address inadvertent disclosures. This article is a reminder that SARs are strictly confidential under federal banking law and violating it has consequences.

What is a SAR?

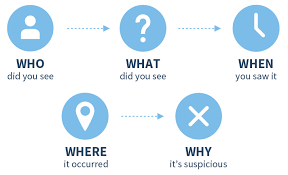

The SARs reporting system became operational on April 1, 1996, under the authority of the Bank Secrecy Act. A SAR is a report by a depository institution to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN, of a financial transaction that may be linked to a crime, such as money laundering, counterfeiting or even terrorism financing. The Treasury Department, under the BSA, extends the filing requirement to any director, officer, employee, or agent of financial institutions. See 31 U.S.C. 5318(g); 31 CFR 103.21. Non-bank entities like casinos, that handle large amounts of cash are also required to report suspicious activity. See 31 U.S.C. 5312(a)(2)(x); 31 CFR 103.11(n)(5) and (6). SARs filings are mandatory.

The law provides a “safe harbor” for SARs filers. Under this safe harbor, depository institutions and their employees are provided broad immunity from civil liability for filing SARs or otherwise reporting suspicious activity. An example of suspicious activity is “structuring” which is when a bank customer breaks up a large cash transaction into two or more smaller transactions to evade detection and the reporting thresholds (i.e. $10,000.00) under the BSA. The bank’s broad immunity however may be waived when a SAR is disclosed without authorization. Keeping SARs – or even the existence of a SAR, confidential is thus important to banks.

Possible Criminal Liability for Unauthorize Disclosures

Two well publicized federal criminal cases demonstrate that unauthorized disclosure of SARs may lead to criminal charges. Federal prosecutors in New York charged Natalie Edwards with unauthorized disclosure and conspiracy to disclose SARS involving financial transactions by those under investigation in the Mueller Special Counsel case. See U.S. v. Edwards, Case No. 18MAG8861 (S.D.N.Y). She was a Senior Official at FinCEN who was accused of leaking SARs and other confidential bank documents to BuzzFeed. She pled guilt and was sentenced in 2021 to six months in prison.

John Fry was an IRS analyst who disclosed SARs filed over transactions involving President Trump’s formed attorney Michael Cohen; Fry is alleged to have given five SARs to Michael Avenatti, who is perhaps best know for representing Stormy Daniels. See U.S. v. Fry, Case No. 3-19-70176 (N.D. Cal.). He pleaded guilty in 2019 and was sentenced to five years of supervised probation and ordered to pay a $5,000 fine.

Some Litigation Best Practices When Representing Banks or Other SARs Filers.

Depository institutions will have a SARs or Anti-Money Laundering program in place. Outside counsel for these clients should become familiar with such policies and prepare for litigation that might raise a SARs issue. Special preparation must be done to address questioning on SARs. With that general knowledge, here are some things to keep in mind during litigation and, specifically, discovery:

- It is illegal to notify any person involved in a suspicious transaction that a SAR has been filed;

- Banks are prohibited from complying with any subpoena that requests disclosure of a SAR;

- During depositions, witnesses should be prepared to allow counsel time to object on the basis of SARs confidentiality and privilege (and perhaps the Bank Examination Privilege) and then maintain the privilege by instructing the witness to refuse to answer the question;

- The witness must not answer a question regarding SARs in any way; keep in mind, the witness may or may not know that a SAR exists;

- SARs questions should be handled by counsel only, who should be prepared with an explanation that neither admits nor denies the existence of a SAR and cites applicable regulations;

- Depending on the bank’s policies, a bank employee may be subject to termination of employment for answering questions that waive a privilege or reveal the existence or substance of a SAR and thereby risk waiving SAR immunity.

- If the existence of a SAR is disclosed inadvertently during a deposition, outside counsel should halt the questioning, have the court reporter mark and segregate the portions of the transcript with the SARs related testimony, pending a stipulation or protective order redacting such testimony, and notify in-house counsel or the bank’s compliance officer.

Is your bank’s outside counsel certified as a Bank Service Provider by the American Bankers Association? Many of the litigators at Michael Best are certified and, in addition, have decades of experience representing banks, financial services companies, insurers, and many types of non-bank lenders. Contact John D. Finerty, Jr. at (414) 225-8269 or jdfinerty@michaelbest.com for more information.

What Documents Are Protected?

The Bank Examination Privilege covers documents or information reflecting the opinions, deliberations or recommendations of governmental bank regulatory agencies. Documents authored by bank examiners are generally covered; but also, documents concerning or referring to materials authored by or sent to bank examiners must be examined closely for a privilege determination. Even internal bank documents that have never been shared with regulators may be subject to the Bank Examination Privilege if they contain or reflect information or communications that are subject to the Privilege.

Examples of documents that likely fall within the scope of the Bank Examination Privilege include, but are not limited to:

- Bank Examination Reports.

- Memoranda of Understanding with bank regulators and communications leading to such Understanding.

- Communications relating to bank supervision - including the Bank’s response to a regulator’s opinion.

The Bank Examination Privilege ordinarily does not cover:

- Purely factual matter that does not reflect opinions, deliberations or recommendations of a bank regulator.

- Requests for information from a bank regulator.

- Bank documents prepared for other purposes and later shared with a bank regulator.

- Documents prepared for or sent to a bank regulator that are not related to a bank examination or supervisory activity.

What is the Bank’s Policy on Disclosure?

No documents or information subject to the Privilege should be produced unless the Privilege is specifically waived by the regulator or ordered by a court after review. In fact, the production of certain categories of materials subject to the Privilege may constitute a crime. It is the responsibility of the Bank and its outside counsel to preserve the Privilege when responding to any subpoena or request for production of documents in litigation or demand for information from a non-banking government agency. Counsel should notify the regulator of the request or demand and then, typically, file protected documents under seal for an in camera review by a court to decide whether the documents will be produced. See In re Subpoena Served on Comptroller, 967 F.2d at 634-635.