As discussed below, the primary provision (and by far the most expensive) is a one-time direct cash payment equal to $1,200 for individuals with adjusted gross income (AGI) of $75,000 or less (or $112,500 or less if filing status is head of household) and $2,400 for couples filing jointly with AGI of $150,000 or less. The payments are increased by $500 for each qualifying child. Beyond the noted income levels, the payment amounts begin to phase out, until the payments are eliminated completely (i.e., no payment is available) at $99,000 of AGI for single taxpayers without children and $198,000 of AGI for taxpayers filing joint returns without children.

The remaining provisions generally enhance the ability of taxpayers to obtain prompt federal income tax benefits from certain deductions, particularly (1) certain charitable contributions made in cash during 2020; (2) net operating (business) losses generated in 2018, 2019 and 2020, which can now be carried back in full to the preceding five taxable years to obtain refunds of income taxes paid in those earlier years; (3) certain “excess business losses” of individuals generated in 2018, 2019 and 2020; and (4) certain business interest expenses. It should be noted that the following summaries relate solely to federal taxes, and do not address the potential adoption of these provisions by states that have income taxes. In general, the legislatures of each state will have to decide whether, and to what extent, they adopt (or, as the case may be, exclude) these provisions. Taking Wisconsin as an example, based on the Wisconsin statutes as currently in effect, none of the provisions discussed below would apply for Wisconsin purposes.

The CARES Act provides for a one-time direct cash payment equal to $1,200 for individuals with adjusted gross income of $75,000 or less (or $112,500 or less if filing status is head of household) and $2,400 for couples filing jointly with adjusted gross income of $150,000 or less. The payment amount is increased by $500 for each qualifying child. To the extent that an individual’s or couple’s adjusted gross income exceeds the thresholds above for their respective filing status, the payment amount is reduced by 5% of the excess until the payment amount is equal to zero.

According to an estimate prepared by the Joint Committee on Taxation, this provision is expected to reduce federal income tax revenues by approximately $292 billion.[2]

[2] The revenue estimates prepared by the Joint Committee on Taxation that are cited throughout this Update are available at: https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5252.

Example #1:

Filing Status |

Single |

|

|

Qualifying Children |

None |

|

|

Adjusted Gross Income |

$75,000 or Less |

$87,000 |

$99,000 or more |

Cash Payment |

$1,200 |

$600 |

$0 |

Example #2:

Filing Status |

Head of Household |

|

|

Qualifying Children |

None |

|

|

Adjusted Gross Income |

$112,500 or less |

$124,500 |

$136,500 or more |

Cash Payment |

$1,200 |

$600 |

$0 |

Example #3:

Filing Status |

Married Filing Jointly |

|

|

Qualifying Children |

None |

|

|

Adjusted Gross Income |

$150,000 or less |

$174,000 |

$198,000 |

Cash Payment |

$2,400 |

$1,200 |

$0 |

Example #4:

Filing Status |

Married Filing Jointly |

|

|

Qualifying Children |

Two (2) |

|

|

Adjusted Gross Income |

$150,000 or less |

$184,000 |

$218,000 |

Cash Payment |

$3,400 |

$1,700 |

$0 |

Section 2204 – Limited Above-the-line Deduction for Individuals

Prepared by Elizabeth Prendergast

Section 2204 of the CARES Act allows individual taxpayers who do not itemize deductions (i.e., those who take the standard deduction) to deduct up to $300 of cash contributions made in taxable years beginning in 2020 to qualifying charitable organizations. A “qualifying charitable organization” is described in Internal Revenue Code (IRC) § 170(b)(1)(A) and includes all charitable organizations to which donations are normally deductible, other than supporting organizations (as defined in § 509(a)(3)) and donor advised funds (as defined in § 4966(d)(2)). Excess charitable contributions that have been carried over from prior years are not eligible for the new above-the-line deduction.

Historically, charitable deductions have been below-the-line deductions, meaning only taxpayers who itemized their deductions could deduct charitable contributions. Charitable deductions have declined drastically in recent years, due, at least in part, to a substantial increase in the amount of the standard deduction under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) thereby resulting in more taxpayers taking the standard deduction instead of itemizing. This CARES Act amendment is intended to incentivize more taxpayers to provide support for charitable organizations as they face increasing demands in service alongside projected declines in giving due to a slowing economy – in addition to the decline in giving they saw following enactment of the TCJA. Nonprofit advocate groups will likely push for a greater limit to the above-the-line deduction in Phase 4 of the CARES Act.

According to an estimate prepared by the Joint Committee on Taxation, this provision is expected to decrease federal income tax revenues by approximately $1.5 billion.

Section 2205 – Temporary Increases in the Caps on Annual Contribution Limits

Prepared by Elizabeth Prendergast

Section 2205 of the CARES Act temporarily raises certain existing limits on the amount of cash charitable contributions that individuals and corporations may deduct. Individuals who itemize may deduct 100% of “qualified contributions,” capped by the amount of their adjusted gross income (AGI), less the amount of all other charitable contributions allowed under IRC § 170(b)(1). This individual deduction cap is increased for 2020 from the usual maximum of 60% of the taxpayer’s AGI. Charitable contributions that exceed the cap may be carried over for the next five tax years. For this purpose, “qualified contributions” means contributions that are made in cash to an organization that is described in § 170(b)(1)(A), and includes all charitable organizations to which donations are normally deductible, other than supporting organizations (as defined in § 509(a)(3)) and donor advised funds (as defined in § 4966(d)(2)).

For corporations, the increase with respect to “qualified contributions” (as defined above) is from 10% to 25% of taxable income, less the amount of all other charitable contributions allowed under § 170(b)(1), with a similar five year carry over allowance for excess contributions. The limit on food inventory contributions by corporations under § 170(e)(3)(C) is increased from 15% to 25%.

The new provision is “elective.” Furthermore, in the case of partnerships and S corporations, the election is made separately by each partner or shareholder. At this time, there is no guidance concerning how these elections are made, although the election presumably will be made on the individual’s 2020 income tax return.

Section 2205 applies only to qualified contributions made in calendar year 2020. According to an estimate prepared by the Joint Committee on Taxation, this provision is expected to decrease tax revenues by approximately $1.1 billion.

Section 2303 – Modifications for Net Operating Losses

Prepared by Thomas Pranica

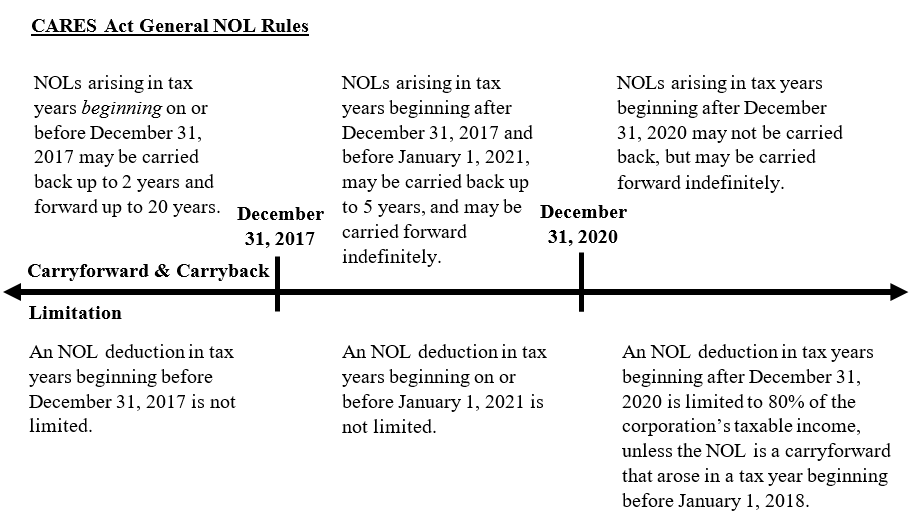

The CARES Act amends the rules regarding net operating losses (NOLs) to: (1) provide that NOLs generated in taxable years beginning in 2018, 2019 and 2020 can be carried back for up to five taxable years; and (2) delay, until 2021, the rule that limits the deduction of an NOL carryforward to 80% of taxable income.

These amendments will allow many taxpayers to more quickly monetize their NOLs. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that these changes will result in revenue decreases of approximately $80 billion in 2020 and $8.6 billion in 2021. Because NOLs deducted during the five-year carryback period will not be available to be carried forward, however, the revenue impact to a significant extent relates to timing. For this reason, the Joint Committee estimates that there will be substantial revenue increases in in 2022 –2030, but that the net tax impact for 2020 – 2030 overall is estimated to be a tax decrease of approximately $25.5 billion.

The following describes the treatment of NOLs prior to and after the CARES Act and practical considerations for taxpayers with respect to the changes.

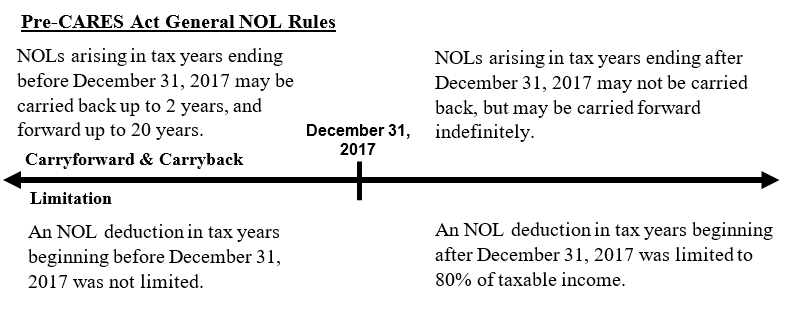

1. Tax Years Ending Before December 31, 2017. Historically, NOLs incurred in tax years ending before December 31, 2017 generally could be carried back up to two years prior to the year of the loss and, to the extent not used, carried forward for up to twenty years. To the extent that the carry back of an NOL reduced the amount of tax due that had already been paid in a prior year, a taxpayer could obtain a refund for the prior year.

2. Changes Made by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Under the TCJA, an NOL incurred in a tax year ending after December 31, 2017 generally could not be carried back but could be carried forward indefinitely. In addition, the deduction of an NOL arising in a tax year beginning after December 31, 2017 was limited to 80% of the taxpayer’s taxable income (determined without regard to the NOL deduction).

3. The CARES Act.

a. Five-Year Carryback. The CARES Act provides that NOLs from tax years beginning after December 31, 2017 and before January 1, 2021 (i.e., tax years beginning in 2018, 2019 and 2020) may be carried back up to five years. Thus, for example, an NOL from the 2018 tax year could be carried back to 2013. The general rules applicable to the carryback of NOLs continue to apply. When carried back, an NOL is applied first to the earliest carryback year prior to the year the NOL is created and the unused balance, if any, is carried forward to the next subsequent year. Additionally, a corporation may irrevocably waive the carryback of an NOL by making an election by the due date (including extensions) for filing the tax return for which the election is to be in effect.

b. Delay of the 80% Limitation. The CARES Act retroactively delays the application of the 80% limitation. Under the Act, the 80% limitation applies only to tax years beginning after December 31, 2020 and only with respect to NOLs arising in tax years beginning after December 31, 2017. Thus, for tax years beginning in 2018, 2019 and 2020, the 80% limit does not apply. For example, an NOL created in 2020 will not be subject to the 80% limitation if it is carried back to prior years; however, to the extent any portion is carried forward to 2021, the ability to use the carryforward portion will be limited to 80% of the corporation’s 2021 taxable income.

The Act also adds that for tax years beginning in 2021 and forward, taxable income for purposes of applying the 80% limitation is determined not only without regard to the NOL deduction, but also without regard to the qualified business income deduction under IRC § 199A and the deduction under IRC § 250 (relating to foreign derived intangible income and global-intangible low tax income). However, taxable income will be reduced by NOLs carried forward from tax years beginning before January 1, 2018.

c. Technical Fix to the TCJA with Respect to Tax Years Beginning Before and Ending after January 1, 2018. The NOL rules were commonly critiqued for a purported oversight in the 2017 TCJA which caused carrybacks to be disallowed for fiscal tax years that began in 2017 and ended in 2018. The CARES Act retroactively amends the effective date of the carryback rules enacted in the TCJA to apply first to tax years beginning after December 31, 2017. Thus, an NOL arising from a tax year beginning before and ending after January 1, 2017 may be carried back and applied to the two prior years. The CARES Act allows a corporation 120 days from the effective date of the CARES Act (from March 27, 2020) to file a “quickie” § 6411 carryback application with respect to such tax periods.

d. IRC § 965. Corporations subject to the deferred foreign income inclusion under the IRC § 965 transition tax enacted by the TCJA are deemed under the CARES Act to make an election pursuant to § 965(n) to not use an NOL to offset such income. The corporation may elect to exclude years in which there is a § 965 inclusion from the five-year carryback period under the CARES Act. The election must be made by the due date (including extensions) for filing the corporation’s first tax return following the enactment of the Act.

e. Farming Losses, Insurance Companies and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). Special NOL rules exist with respect to farming losses, insurance companies and real estate investment trusts (REITs). Previously, farming losses and the losses of certain insurance companies could be carried back two years. Under the CARES Act, such losses during the relevant period will also be eligible for the five-year carryback. If a life insurance company’s loss is carried back to a tax year beginning before January 1, 2018, such loss shall be treated as an operating loss (in accordance with § 810 prior to its repeal). Also under the Act, a REIT generally may not carryback any losses.

f. S Corporations and Partnerships. The CARES Act amendments relating to the five-year carryback and the 80% limitation apply to C corporations, and to shareholders of S corporations and partners of partnerships (and members of LLCs treated as partnerships for income tax purposes). In the case of such shareholders, partners and members, however, taxpayers should be aware of the long-standing rules relating to tax basis, at-risk and passive losses, which in some cases may limit or eliminate the ability to claim the losses as deductions.

Client Considerations

- As noted above, the CARES Act corrected a technical problem in the TCJA, which had prohibited the two-year carryback (under pre-TCJA law) of NOLs from fiscal years that began before and ended after January 1, 2018. The CARES Act provides that taxpayers with NOLs from that fiscal year may, within 120 days after the enactment of the Cares Act (i.e., within 120 days after March 27, 2020), file a “quickie” carryback application pursuant to IRC § 6411. Accordingly, taxpayers who may be in this position should promptly review with their tax advisors the possibility of filing such a carryback application. Note that, because the TCJA generally lowered corporate income tax rates from 35% to 21% (first effective in 2018) it may be particularly beneficial to carry an NOL back to pre-2018 years.

- To the extent not yet filed, taxpayer

’s should analyze their 2019 tax return to consider the application the CARES Act’s NOL modifications. Carrybacks of NOLs arising in 2019 should not be limited to 80% of taxable income. Refunds of prior year taxes should also be available with respect to NOLs arising in 2019 pursuant to the abbreviated process set forth under IRC § 6411(a). Taxpayers should analyze with their tax advisors both whether and when to pursue refunds attributable to 2018 and 2019 NOLs, especially taxpayers with prior § 965 inclusions.

- As mentioned, taxpayers with NOLs arising in tax years beginning in 2018 may also be entitled to refunds. With respect to process, however, the CARES Act does not specifically provide that a refund may be claimed pursuant to the “quickie” method under IRC § 6411(a) with respect to NOLs incurred in the 2018 year. Generally, the abbreviated § 6411 process is only available if the application is filed within twelve months of the tax year in which the NOL arises. Accordingly, subject to future IRS guidance, claiming a benefit with respect to NOLs arising in 2018 may require filing amended tax returns (on Form 1120X or 1040X, as the case may be) to carry back such losses. This is generally a slower process than the § 6411 “quickie” procedure, and may, if the claimed refund is sufficiently large, require review by the Joint Committee on Taxation pursuant to § 6405 prior to the grant of the refund (the thresholds are $5 million in tax in the case of C corporations; $2 million otherwise). Given the clear and compelling legislative intent of allowing taxpayers with NOLs to quickly monetize these losses, we would expect that, whether the § 6411 procedure is available or not, the IRS would quickly process NOL carryback claims.

- NOLs arising in 2020, which are widely expected to occur as a result of the Coronavirus pandemic, will not provide a benefit to taxpayers until after the close of their 2020 tax year. Once the 2020 tax return is filed, however, such losses may be carried back using the “quickie” refund process under IRC § 6411(a) to the preceding five years, potentially providing taxpayers with refunds.

- To the extent taxpayers can permissibly do so, they should consider accelerating to 2020 deductions that might otherwise be incurred in 2021 or later years. Doing so would potentially result in a larger 2020 loss, which might then be carried back up to 5 years to quickly monetize the loss (possibly with respect to pre-2018 years, when the tax rate for many taxpayers was higher than post-2017 rates).

- The elimination by the TCJA of the carryback of NOLs generated in post-2017 years resulted in situations where target C corporations with large expenses in the year of sale (due to transaction costs, cash-out of stock options, payouts of compensation, etc.) had year of sale NOLs that could not be carried back (only forward). Often, applicable transaction documents provide that pre-closing tax benefits are for the benefit of the selling shareholders. Accordingly, selling shareholders who may be in this position should consult with their tax advisors about the possibility of filing NOL carryback claims, which are now allowed under the CARES Act for NOLs incurred in taxable years beginning in 2018, 2019 and 2020.

- The CARES Act’s modifications to the NOL rules may significantly impact the calculation of other tax credits and deductions, both prospectively and retrospectively. Further, the NOL rules may impact business’s financial reporting positions with respect to deferred tax assets and valuation allowances. Taxpayers should carefully analyze the tax and accounting implications associated with the modifications to the NOL rules and should model how such changes will impact prior tax returns, prior to making NOL claims.

Section 2304 – Modification of Limitation on Losses for Taxpayers other than Corporations

Prepared by Thomas Pranica

The CARES Act amended the rules regarding the allowable amount of business loss that a noncorporate taxpayer (i.e., generally an individual) may deduct to reduce their federal income tax liability. The amendment should remove obstacles that prevented individuals from deducting certain “excess business losses” (EBLs) for taxable years beginning in 2018, 2019 and 2020.

Due to changes made by the TCJA, an individual could not deduct an EBL in tax years beginning after December 31, 2017 and before January 1, 2026. An EBL is the amount by which the aggregate deductions attributable to a taxpayer’s trades or businesses exceed the related aggregate gross income or gain attributable such trades or businesses plus $250,000 ($500,000 for joint returns), indexed for inflation. The EBL limitation is applied after the passive activity limitations under IRC § 469.

The CARES Act retroactively delays the EBL limitation to start with tax years beginning after December 31, 2020. Thus, the Act makes the EBL limitation applicable only with respect to tax years beginning after December 31, 2020 and before January 1, 2026.

The Act also made adjustments to clarify the calculation of an EBL and the ability to carry forward EBLs. The Act specifies that the EBL limitation is determined without regard to any deductions, gross income, or gains attributable to any trade or business of performing services as an employee (an issue that had been the subject of some dispute). Further, the calculation of an EBL excludes deductions with respect to the allowable NOL deduction under IRC § 172, the qualified business income deduction under IRC § 199A, and losses from the sale or exchange of capital assets. The calculation includes gains from the sale or exchange of capital assets to the extent of the lesser of the taxpayer’s net capital gain income (i.e., capital gains less capital losses) or the net capital gain income attributable to trades or businesses. The Act also allows for EBLs to be carried forward as an NOL to subsequent years, as opposed to merely being able to be carried forward to the next following year.

To the extent that a taxpayer incurred a loss that was subject to the EBL limitation in 2018, the taxpayer should consider seeking a refund with respect to such loss to the extent it could have offset other non-business income. As to 2019 returns, they should be prepared without regard to the EBL limitation, potentially reducing tax or resulting in larger losses. EBLs incurred in 2020, of course, would be reflected on the taxpayer’s income tax return filed in 2021, and would either reduce tax for 2020, or increase the 2020 loss, as the case may be.

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, this amendment is anticipated to decrease tax revenues by approximately $74.3 billion in 2020 and $66.2 billion in 2021. Between 2020 and 2030, this amendment is anticipated to result in an overall decrease in tax revenues of approximately $169.6 billion.

Section 2305 – Modification of Credit for Prior Year Minimum Tax Liability of Corporations

Prepared by Thomas Pranica

Pursuant to the TCJA, the corporate alternative minimum tax (AMT) was repealed for tax years beginning after December 31, 2017. Unused AMT credits, however, were permitted to be carried forward to subsequent years and applied against a corporation’s regular federal income tax liability. Additionally, a portion of the AMT credits were refundable. The portion of AMT credits that were refundable was limited to 50% of the amount of excess credits for tax years 2018, 2019 and 2020, and was limited to 100% for tax year 2021.

The CARES Act adjusts the timing with respect to the refundable AMT credits. Under the Act, refundable AMT credits are limited to 50% of the amount of excess credits for tax year 2018, and are limited to 100% for tax year 2019. The Act also provides corporations with an election to take the entire amount of refundable credits in 2018. The Act states that if the election is filed prior to December 31, 2020, an application for tentative refund should follow the same general procedure as the “quickie” refund process under IRC § 6411(a). The Act states that, within 90 days after a properly completed application is filed, the IRS must review the application, determine the amount of overpayment and apply, credit or refund such overpayment.

Corporations should analyze if it is better to receive the benefit of their refundable AMT credits by way of the election with respect to the 2018 tax year, or as a matter of course by filing their 2019 tax return, if they have not already done so.

According to a revenue estimate prepared by the Joint Committee on Taxation, this provision will have no revenue impact for the 2020 – 2030 period. That is because it is expected that the amount of AMT credits that would have been claimed in 2021 (approximately $3.2 billion) would instead be claimed in 2020.

Section 2306 – Modification of Limitation on Business Interest

Prepared by Daniel LaFrenz

Pursuant to the TCJA, for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017, a business interest expense deduction is generally limited to the sum of the business interest income of the taxpayer, plus 30% of such business’s “adjusted taxable income,” plus the amount of certain floor plan financing interest. Any amount of interest expense not allowed as a deduction could be carried forward indefinitely (but subject to the same 30% limitation). The limitation is subject to a number of exceptions, including an exception for businesses with gross receipts under a certain threshold and an exception for certain regulated public utilities. In addition, certain businesses can elect out of the limitation, such as real property and farming businesses (although such electing businesses are then not eligible for 100% bonus depreciation under § 168(k) for certain assets).

Under the CARES Act, in the case of businesses that were subject to the 30% business interest expense deduction limitation, the limitation is increased to 50% of such businesses’ adjusted taxable income for any taxable year beginning in 2019 or 2020 (and is further subject to a special rule for partnerships, discussed below). The prior 30% limitation continues to apply to such businesses for any taxable year beginning after 2020. In addition, under the CARES Act, a business can elect to use its 2019 adjusted taxable income for purposes of computing the 50% interest expense deduction limitation in 2020. In other words, if a business’s 2019 adjusted taxable income would produce a larger allowance than a business’s 2020 adjusted taxable income, such business would likely benefit from making the election.

For example, a business that was profitable and had $1,000,000 of adjusted taxable income in 2019 but computed a taxable loss (NOL) in 2020, could deduct up to $500,000 of business interest expense in each of 2019 and 2020 notwithstanding that such business had a negative adjusted taxable income amount in 2020. In this example, assuming that the business has sufficient interest expense in each year, the election could benefit the business by generating a larger NOL in 2020, and that increased NOL can then be carried back and applied against its taxable income reported in the five prior years under the new NOL carryback rules discussed above.

In the case of a partnership subject to the interest expense limitation, the new 50% limitation does not apply to a taxable year that began in 2019. In that case, the partnership would determine the deduction for interest expense at the partnership level based on the 30% limitation and allocate any disallowed portion of the interest expense to its partners, which the partners must generally carry forward to future taxable years subject to certain limitation rules. For taxable years beginning in 2020, unless a partner elects otherwise, the interest expense limitation rules will not apply to 50% of the partner’s allocable share of the partnership’s 2019 disallowed interest expense that the partner carried forward to 2020. In addition, for taxable years beginning in 2020, the new 50% limitation applies to a partnership that is subject to the interest expense limitation.

Finally, a business may elect out of the new 50% limitation rules. This election is irrevocable without the consent of the Secretary. Due to the interplay of the interest expense deduction limitation rules and other tax rules, it will be important for a business to analyze the impact of the increased 50% interest expense deduction limitation to determine whether the 50% limitation will produce a favorable tax position or whether the business would be better served by electing out. For example, a business subject to base erosion and anti-avoidance tax (BEAT) may, under certain circumstances, benefit from an election out of the new limitation rules because the election would reduce its currently deductible expenses (thereby potentially avoiding the BEAT minimum tax while also preserving the possibility of deducting the disallowed interest expense in future years through the indefinite carry forward of any disallowed interest expense deduction).

The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that this provision will result in a decrease to federal income tax revenues of approximately $13.4 billion.

Section 2307 – Technical Amendments Involving Qualified Improvement Property

Prepared by Jonathan Luljak

The CARES Act also corrects an oversight in the TCJA relating to certain bonus depreciation rules under IRC § 168(k) applicable to real estate, restaurant, retail and related-industry businesses.

Prior to TCJA, the bonus depreciation rules granted businesses a deduction for certain capital investments in an amount equal to 50% for the initial year when placed in service, and the remaining 50% over a 15-year period. Outside of these rules, the IRC otherwise required businesses to capitalize and deduct such expenses over longer periods of time, sometimes up to forty years. Property eligible for bonus depreciation included (1) qualified leasehold improvement property; (2) qualified restaurant property; (3) qualified retail improvement property; and (4) owner-occupied nonresidential property.[1]

TCJA sought to simplify and expand the bonus depreciation rules by creating a new, single category known as “qualified improvement property,” which is generally defined as any improvement to an interior of a nonresidential building that is placed in service after the building was placed in service, and includes the four categories described above among additional types of property. TCJA also permitted businesses to deduct 100% of the capital expenditure in the year when placed in service beginning after December 31, 2017. Due to a drafting error, however, the statutory language failed to include this new category under the types of property eligible to take the 100% deduction. In effect, the TCJA inadvertently made the depreciation rules much worse for these types of real estate-centric businesses as the depreciation period actually increased to 39 years.

As part of the CARES Act, Congress has remedied this error in the TCJA. The correction involves adding “qualified improvement property” to the list of “15-year property” under IRC § 168(e)(3)(E). The correction is retroactive, which means that certain impacted taxpayers may be able to amend returns and seek refunds to account for the bonus depreciation on qualified improvement property placed in service after December 31, 2017. The correction is not without faults, however, as partners in certain partnerships that are unable to (or if able, do not) elect out of the partnership audit rules enacted by Congress in 2015 will need to wait to file a 2020 return to benefit from this change (as refunds for prior tax years are now treated as adjustments to a partner’s income under its next return).

With regard to claiming refunds for the periods covered by the retroactive change, it is unclear at this time whether the taxpayer may do so simply by filing an amended return, or whether the taxpayer must file a request with the IRS to change its accounting method (typically done on IRS Form 3115) with respect to the qualified improvement property. The Treasury Department and IRS are aware of this question, and it is hoped they will issue guidance, consistent with the purpose of the CARES Act, to allow taxpayers to monetize the additional deductions as quickly as possible.

The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that this technical correction will have no revenue impact, presumably because the revenue impact was previously included in the TCJA estimates.

Section 2308 – Temporary Exception from Excise Tax for Alcohol Used to Produce Hand Sanitizer

Prepared by Robert Gordon

Distilled spirits produced in or imported into the United States are subject to an excise tax computed on a per-gallon basis. Distilled spirits on which the excise tax has not been paid may only be removed from the premises of a distillery under certain exceptions specified in the IRC. Section 2308 of the CARES Act creates a temporary new exception to allow removal of distilled spirits from a distillery at any time during calendar year 2020 without payment of the tax, if they are used in or contained in hand sanitizer produced and distributed in a manner consistent with guidance issued by the Food and Drug Administration related to the COVID–19 outbreak.

The purpose of the provision is to permit distilleries to immediately begin producing hand sanitizer with their alcohol on hand without having to pay excise tax on that alcohol, and without first having to go through the regulated process of “denaturing” the alcohol (i.e., making it unfit for human consumption) in order to gain exemption from the tax under a different exception. Consistent with this purpose, the provision also exempts hand sanitizer produced under the provision from certain statutes in the Federal Alcohol Administration Act governing labeling and bulk sales.

[1] The law prior to the TCJA only permitted 50% of the cost of owner-occupied nonresidential property to be deducted in the initial year, and thereafter required such capital expenditures be deducted according to its ordinary lifespan.